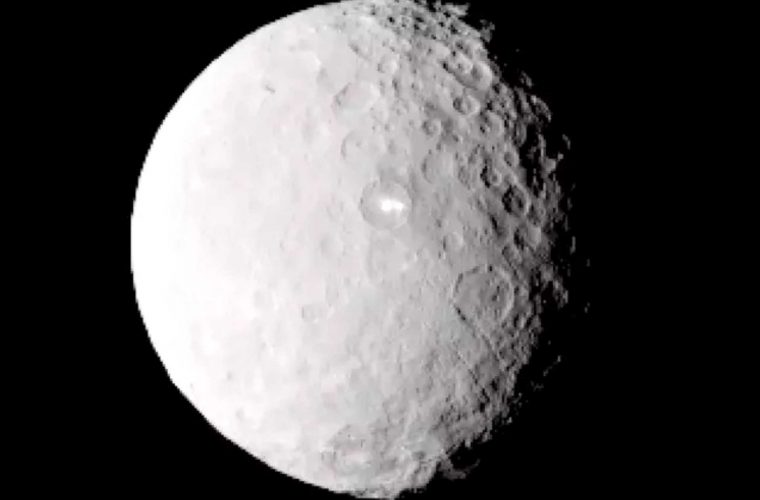

Ceres, the biggest article in the space rock belt among Mars and Jupiter, is a “ocean world” with a major supply of pungent water under its freezing surface, researchers said in discoveries that raise enthusiasm for this diminutive person planet as a potential station forever.

Examination distributed on Monday dependent on information acquired by NASA’s Dawn rocket, which flew as close as 22 miles from the surface in 2018, gives another comprehension of Ceres, including proof showing it remains geographically dynamic with cryovolcanism – volcanoes overflowing frosty material.

The discoveries affirm the nearness of a subsurface store of brackish water – salt-enhanced water – leftovers of a huge subsurface sea that has been bit by bit freezing.

“This elevates Ceres to ‘ocean world’ status, noting that this category does not require the ocean to be global,” said planetary researcher and Dawn head examiner Carol Raymond. “In the case of Ceres, we know the liquid reservoir is regional scale but we cannot tell for sure that it is global. However, what matters most is that there is liquid on a large scale.”

Ceres has a breadth of around 590 miles. The researchers concentrated on the 57-mile-wide Occator Crater, shaped by an effect around 22 million years prior in Ceres’ northern half of the globe. It has two brilliant zones – salt outsides left by fluid that permeated up to the surface and dissipated.

The fluid, they finished up, started in a saline solution supply many miles wide hiding around 25 miles beneath the surface, with the effect making breaks permitting the pungent water to get away.

The examination was distributed in the diaries Nature Astronomy, Nature Geoscience and Nature Communications.

Other close planetary system bodies past Earth where subsurface seas are known or seem to exist incorporate Jupiter’s moon Europa, Saturn’s moon Enceladus, Neptune’s moon Triton and the diminutive person planet Pluto.

Water is viewed as a key element forever. Researchers need to evaluate whether Ceres was ever livable by microbial life.

“There is major interest at this stage,” said planetary scientist Julie Castillo of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, “in quantifying the habitability potential of the deep brine reservoir, especially considering it is cold and getting quite rich in salts.”